He was called “Stupor Mundi,” the astonishment of the world. Frederick II of Hohenstaufen remains as controversial now as he was when he was emperor of the First Reich, the Holy Roman Empire. He was painted larger than life by his contemporaries, friends, and foes alike, so historians find it difficult to separate fact from fiction. Frederick was a skeptic, a polyglot, and a scientist—a man born in the wrong century. He was acclaimed as the Messiah and feared as the Antichrist at the same time.

Frederick was born in 1194 in Ancona, Italy, and was brought to Sicily upon the death of his father, Emperor Henry VI. At age two, he was crowned King of Sicily and entrusted to the guardianship of Pope Innocent III. After coming of age, Frederick stabilized his Sicilian realm, defeated his German rival Otto IV, and was elected king of Germany in 1212. In 1220, he was crowned emperor, uniting Sicily and Germany in his person. Delaying his promised Crusade to the Holy Land caused the exasperated Pope Gregory IX to excommunicate Frederick, but in 1228, he went anyway and spectacularly regained Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and Nazareth without bloodshed.

Frederick’s military actions in Italy made Gregory fearful that his Papal States would be encircled and excommunicated the Kaiser again in 1239. The titanic struggle between the pope and the emperor culminated with Frederick being deposed by Innocent IV in 1245. In the years following, he lost much of central Italy. Frederick seemed to be on the verge of recovering his fortunes when he suddenly died in 1250.

This brief sketch hardly gives us a picture of the man the medieval world found so fascinating and extraordinary, attracting to himself so many myths and legends. The following list will delve deeper into Frederick’s complex personality.

Related: Top 10 Pieces Of Nazi German Propaganda That Backfired

10 A Very Public Birth

Queen Constance of Sicily was 40 when she became pregnant by Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV. She was an old woman by medieval standards, and doubts about her pregnancy sent tongues wagging. To dispel the rumors, a tent was set up in the public square of Jesi, where the queen was staying, and as soon as she was in labor the day after Christmas, she took to the tent so that she could give birth before witnesses consisting of townspeople, bishops, and cardinals.

The birth of Frederick was hailed as “miraculous and unexpected” by many, but others, unconvinced, said that Constance had faked the whole thing and had been hiding the baby under her dress. The real father, it was rumored, was a local butcher. This story would cause Frederick embarrassment later in life.

It was alleged that the monk Joachim of Fiore, Constance’s confessor, had predicted to Henry IV, “So depraved your child! So bad, your son and heir! Oh my God! He will upset the world and tread on the saints of God!” He described Constance as possessed by the devil and her pregnancy as the herald of the coming of Antichrist. Joachim actually never wrote anything about Frederick, but this tale shows how the emperor’s enemies interpreted the circumstances of his birth in the light of his later career.[1]

9 The Sicilian Court

Sicily lay at the crossroads of civilizations. Colonizing Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans, Byzantines, Arabs, and Normans left their imprints on its life and culture, giving Sicily a unique cosmopolitan air. Frederick grew up in Palermo, a city redolent of learning, where a mix of religions and peoples existed side by side.

This rich diversity instilled curiosity and tolerance in the young king. He learned from scholars, philosophers, artisans, astrologers, merchants, and returning sailors. Frederick was to eventually learn how to speak Arabic, Greek, Latin, Italian, Sicilian, German, and Norman French. He encouraged poetry and literature, and his court’s Sicilian School of Poets favored writing in Italian over Latin, helping to develop the language, ready for use by Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio in the Renaissance.

Frederick encouraged scientific investigation of natural phenomena. He wrote letters asking questions of scientists and mathematicians and conducted experiments himself. It is said that he never believed anything that couldn’t be rationally explained. Desiring an educational institution not influenced by the Pope, he founded the University of Naples in 1224.

Frederick maintained the first great menagerie in Western Europe, including an elephant, white bear, giraffe, leopard, hyenas, lions, cheetahs, camels, and monkeys. Even the laws he passed for Sicily were based on rationality rather than custom or tradition. He banned, for instance, trial by combat in legal disputes. He enacted laws against air and water pollution and required doctors and pharmacists to have licenses.

Frederick was truly a Renaissance man two centuries before the Renaissance.[2]

8 A Secret Muslim?

An enduring controversy about Frederick concerns his faith—or lack of it. Atheists delight in the oft-repeated anecdote (probably untrue) of the Kaiser saying that Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad were deluded impostors. There are those who suggest that Frederick was actually a secret Muslim, and they bring forward reasonable arguments that a Muslim once ruled a Christian empire in the middle of Europe.

We have seen that Sicily had a sizable Arab population of over 30,000, and even though they no longer predominated in Palermo, their culture and religion left lasting traces. Frederick’s maternal grandfather, Roger II, styled himself as an Arab king. Frederick himself developed a high regard for Islamic art, science, and philosophy. He reportedly had a harem guarded by black eunuchs and was entertained by dancing girls like an Oriental despot.

Though he had great respect for Muslims, Frederick did show ruthlessness when they revolted. He determined to rid Sicily of Arabs to forestall any more uprisings, not by massacring them, but by resettling them in Lucera, in Apulia, in southeastern Italy. The city was entirely Muslim, governed by Shari’a law, with mosques and muezzins intoning the daily call to prayer.

Muslim soldiers served alongside German Christians in Frederick’s army. Just 150 miles (241 kilometers) south of Rome, Lucera had Frederick’s protection, and the appalled Pope Gregory mocked him as “Sultan of Lucera.” The emperor’s friendliness toward Muslims during the Sixth Crusade further reinforces suspicions that he was indeed a follower of Islam.

Those who disagree point out that Frederick’s actions were nothing more than the result of shrewd diplomacy and political calculation in his high-stakes struggle against the Papacy.[3]

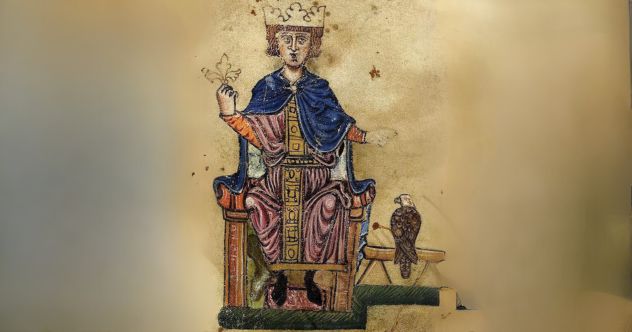

7 Book on Falconry

Frederick loved exotic animals and enjoyed a good hunt. Falcons were trained birds of prey that accompanied hunters, and Frederick was a master in the art of falconry. But he was so dissatisfied with the insufficient literature on the antique sport that he decided to write one himself. His book De Arte Venandi cum Avibus (On the Art of Hunting with Birds or The Art of Falconry) was the most comprehensive work on the subject in the West.

Drawing on his own experiments and years of observations, Frederick demonstrated an encyclopedic knowledge of the ethnology, ecology, morphology, and behavior of birds. It made the book the most important work of empirical zoology in the 13th century. Frederick’s research focused on about 80 bird species. He criticizes Aristotle for accepting hearsay as facts without bothering to confirm them by observation. Frederick backs up his claims with experimental evidence.

In one experiment, he covered the eyes of a vulture to determine if it used its sense of smell to detect prey (it didn’t). Using empirical methods, he also busts myths like barnacle geese being born out of dead wood and ostrich incubating their eggs. Frederick was the first to enunciate Bergmann’s Rule (established by Carl Bergmann in 1847), which stated that warm-blooded vertebrates from colder climates tend to be larger than those in warmer regions.

In his observations on variations within the same species, he muses on some ideas Charles Darwin would later discuss in the theory of evolution. Frederick presents more empirical innovations about ecosystem trophic structures, mate choice behavior, parent-offspring relations, kin selection, and seasonal migration. As a heretic, Frederick’s book was banned by the Church, and it would only be rediscovered in 1788.[4]

6 The Mad Scientist

To the medieval mind, Frederick’s rationality, curiosity, and interest in scientific experimentation were unusual, even sinister. Already notorious as a friend of Jews and Muslims and an implacable enemy of the pope, Frederick’s enemies saw his skepticism as further proof of his demonic nature. A Franciscan monk named Salimbene of Parma reports of chilling human experiments the emperor allegedly performed.

In one, Frederick had a prisoner sealed in a wooden cask and left to die of hunger. A hole was bored into the cask, and as the man approached death, it was carefully observed to determine if the soul could be glimpsed leaving the body. In another, Frederick wanted to know how the digestive process is affected by exercise and sleep. He had two prisoners fed identical dinners. Afterward, one was sent out on a hunt and the other to bed. They were then killed and disemboweled to compare the contents of their stomachs.

In what may be the cruelest experiment of all, for the sake of discovering humankind’s original language, nurses were instructed to raise a group of infants without interacting with them beyond feeding and bathing. Hearing no human speech, it was hoped the babies would revert back to the language of Adam and Eve. Predictably, all the babies died from a lack of nurture and love.

While Frederick had an interest in biology, it is doubtful if he really carried out these insane experiments. It is just one example of his enemies exploiting his fascination with science to paint him as the Antichrist.[5]

5 The Mystery of Castel Del Monte

In Umberto Eco’s medieval murder mystery The Name of the Rose, there is an enigmatic and labyrinthine structure that holds the key to solving the case. Eco appears to have been inspired by the real-life Castel del Monte, one of the many castles Frederick built in Italy. A UNESCO World Heritage site, Castel del Monte poses many mysteries to historians.

Reflecting Frederick’s multicultural values, the castle, begun in 1240, is a blend of classical, Northern European, and Islamic motifs. But what intrigues investigators is that the castle didn’t seem to have any military or defensive function. It is situated on a low hill near Andria in southern Italy. It has no moat nor drawbridge, and the spiral staircases wind counter-clockwise, contrary to the defensive pattern of other castles. There are none of the expected underground passageways. There is no trace of a kitchen that should have fed hundreds of defenders. There is no encircling wall, and the loopholes are too narrow. What was the castle used for, then?

The first thing that strikes a visitor’s attention is the recurrence of the number 8 throughout the building. It is octagonal and has 8 rooms each on the first and second floors. It has 8 smaller octagonal towers at each of the 8 corners. The number 8 is the symbol of infinity and resurrection; historians have looked for astrological, numerological, or other occult meanings.

Interestingly, Frederick had met the mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci, and it must be no coincidence that floors, fireplaces, windows, and even shadows in the octagonal courtyard encode the Fibonacci sequence. The acanthus leaf, a popular symbol in Freemasonry, is a conspicuous decorative motif. A windowless room on the ground floor is thought to have been used for esoteric rituals.

Theorists have put forward links to the Holy Grail, the Pyramids, ratios of musical intervals, Solomon’s temple, and the queen of Sheba. The castle may have been a temple or astronomical observatory. Less fanciful historians think it may have served as nothing more than a hunting lodge for Frederick. Whatever the reasons for Frederick’s obsession with 8, it did not seem to have helped him. He died in 1250 (1+ 2+5+0=8), and his dynasty collapsed 16 (8 + 8) years later in southern Italy. Of course, it may just be a coincidence.[6]

4 The Bloodless Sixth Crusade

At his coronation as Holy Roman Emperor in 1220, Frederick vowed to lead a Crusade to the Holy Land. He didn’t show up for the Fifth Crusade, and the Christian defeat at Damietta, Egypt, in 1221 was partly blamed on his absence. But Frederick wanted to secure his control over Italy first before turning his attention elsewhere. In 1225, he married Isabelle (Yolande) of Brienne, heiress to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, giving him a personal interest in taking the city.

In 1227, Frederick prepared to depart, but an outbreak of disease forced him to delay yet again. Pope Gregory IX had enough of his excuses and excommunicated him, but the emperor was finally on his way the following year. Sultan al-Kamil, having his own troubles with his brother, the emir of Damascus, chose not to confront Frederick’s well-trained and professional force of 10,000 infantry and 2,000 knights. Instead, he negotiated a peace with Frederick that handed Jerusalem over to the Crusaders without a fight.

Frederick entered Jerusalem in triumph. A priest rushed forward with a cross toward the Al-Aqsa mosque, but Frederick shoved him aside and forbade any attempt to convert mosques into churches. In turn, muezzins were ordered by the Qadi of Nablus not to sound the call for prayers. The Muslims were surprised when Frederick expressed disappointment: “You were mistaken by what you did, for God knows that spending the night in Al Quds and hearing the Islamic prayer from the muezzins with their words that praise and thank God was my greatest desire.”

Frederick had fulfilled his vow and was at the pinnacle of power, but Pope Gregory was less than elated: “A great beast has come out of the sea… this scorpion spewing passion from the sting in his tail… full of the names of blasphemy… raging with the claws of the bear and the mouth of the lion, and the limbs and the likeness of the leopard, opens its mouth to blaspheme the Holy Name …behold the head and tail and body of the beast, of this Frederick, this so-called emperor….”[7]

3 Messiah or Antichrist?

The bloodless recapture of Jerusalem stunned Europe. Frederick began to be seen as the fulfillment of eschatological prophecies. Joachim of Fiore had declared the years from 1200 to 1260 would see the culmination of human history. Before the coming of the Age of the Spirit, however, both a Supreme Teacher of holiness and the Antichrist would appear.

Frederick crowned himself king of Jerusalem, well aware of the parallels with Christ being hailed likewise upon his entry into the city. Frederick was now the Messiah, the new David. He believed he had been raised by God in the spirit of Elijah.

Some recalled Virgil’s Fourth Eclogue: “The final age, foretold by Cumaean song, is here… That child, blest with life of the gods, will witness hero and deity once more united, and under their watchful eye, will rule a world restored to peace.” The child born into the “house of Caesar” must be Kaiser Frederick. Frederick’s chancellor Pietro da Vigna portrayed him as a Cosmocrator, a Cosmic Savior, with “an undoubted gift to unite all parts of the Universe together, reconciling heat and cold, solid and liquid, in a word, all opposites.”

The Pope and Frederick’s enemies saw things differently. The emperor’s hostility to the Church and friendship with Islam were surely the marks of the Antichrist. “What other Antichrist should we await, when as evident in his works, he is already come in the person of Frederick?” asked Pope Gregory. The emperor and the Pope continued their apocalyptic see-saw struggle. As 1260 approached, events seemed set for their prophesied climax when Frederick unexpectedly died.[8]

2 Frederick Is Alive!

Frederick came down with dysentery in early December 1250 and died on the 13th. His Muslim bodyguards escorted his remains to Palermo Cathedral, where it was buried in a sarcophagus. Pope Innocent IV, Gregory’s successor, was wild with delight: “Let heaven exult and the earth rejoice!” Nicholas of Carbio was gleeful that the “tyrant and son of Satan” was dead, “deposed and excommunicated, suffering excruciatingly from dysentery, gnashing his teeth, frothing at the mouth.”

Frederick’s supporters were in shock. How were the messianic prophecies to be fulfilled? A minority, both friend and foe, began to believe that the Kaiser was not really dead but hidden away elsewhere, biding his time. A monk was reported to have seen Frederick, with an army of knights, descend into the fiery bowels of Mt. Etna, where he would emerge for the final showdown. A prophecy circulated: “His death will be hidden and unknown, among the people will resound:‘He lives’ and ‘He does not live.’”

Most people accepted that Frederick was dead, but they awaited his resurrection to fulfill his destiny. This belief was exploited by one Tile Kolup, who appeared in 1284, claiming he was Frederick, and proceeded to set up court in the city of Neuss. He issued decrees as Frederick for a time, and the German king Rudolph I set out to put the pretender out of commission. Pseudo-Frederick was captured at Wetzlar, tortured, and executed.

As apocalyptic fervor receded, Frederick was finally left to rest in peace. But his long shadow reached out across the following ages to touch the 20th century.[9]

1 Frederick and the Nazis

Frederick was a Dr. Jekyll/Mr. Hyde-like character even while alive. After his death, myths about him were used and abused for political purposes and molded according to the agenda. For some, he was a tolerant ruler and pacifist with modern ideas, but some ominously see in him “a model for a totalitarian state.” It was this Mr. Hyde image that Adolf Hitler and the Nazis exploited for their ends.

In 1927, German-Jewish historian Ernst Kantorowicz published his massive biography of Frederick, describing him in mythic, almost idolatrous, terms: “Savior and Antichrist in one… the first godless man, the first man to be divine in nature, and the first man holy not through the Church.” It was rather unfortunate that Kantorowicz chose to put the Hindu symbol of good luck on the cover—the swastika.

Though not Kantorowicz’s intent, the Nazis used his book to present Frederick as a symbol of German rebirth, ethnicity, and identity—the Ubermensch. The Third Reich was legitimized as the historical continuation of the First and Second Reichs. Hermann Goering gave the book as a gift to Mussolini, and Himmler kept a copy by his bedside. Hitler enthused, “What courage they must have had! How many times did they cross the Alps on horseback! Men of caliber, who have ruled over Sicily no less!”.

On New Year’s Day 1941, Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop presented Hitler with a scale model of Castel del Monte. Determined to follow in Frederick’s martial footsteps, Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union later that year was codenamed “Barbarossa” after Frederick’s grandfather. The 9th SS Panzer Division was named Hohenstaufen, after Frederick himself. Several days before General George Patton was to launch the Allied invasion of Sicily in 1943, Goering ordered Frederick’s body removed from its sarcophagus in Palermo and brought to Germany. It was ignored.

Kantorowicz, who had fled to England, was dismayed at how the Nazis had used his book. To his wife, he said, “That’s a book, my dear child, that I myself do not understand.” [10]